My Santayana Sampler

I am way too curious and restless to be monogamous in my literary passions

For self-evident reasons, today’s is longer than six hundred words. For your summer hammock perhaps…

When dull or sad, I scribble in my journal. I begin without an idea except to report my whereabouts or perhaps to recount some memorable words composed by others. Thoughts kindle thoughts. I would not call this inspiration but extraction. Insights invariably follow from what’s preceded, as curiosity noses for something new: not an “a-hah” but an “uh-huh.” Felicity may or strike or not, in either case an accident.

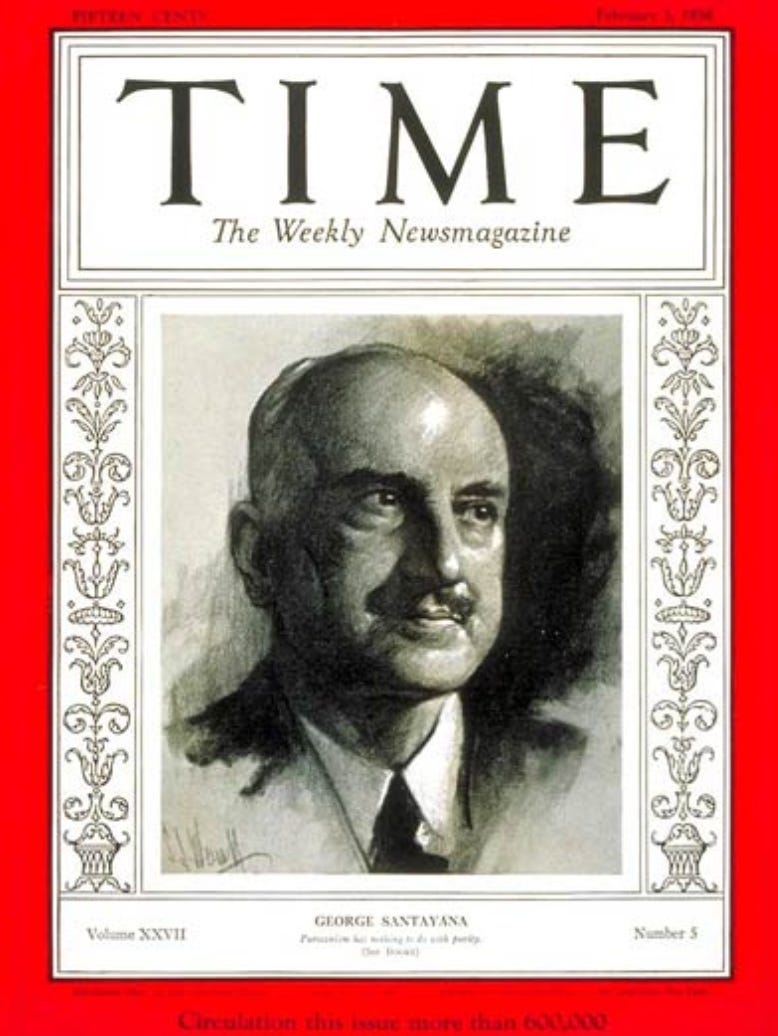

I’ve just finished performing such an extraction on George Santayana’s hefty autobiography, Persons and Places. I have written often about Santayana in different contexts. He composed my favorite sentence in English: "That life is worth living is the most necessary of assumptions, and were it not assumed, the most impossible of conclusions." In Rome, where he closed his long life and is buried, he loomed larger. I knew various of the makers who’d known him, two in person. Wallace Stevens’ poem, “To an Old Philosopher in Rome,” haunted me.

Our relationship was complicated, as intimacies tend to be. Why was I drawn to this lonely, somewhat prissy, bygone soul? Only of aphorisms was he a writer of genius; his prose and poetry were merely good. His novel, The Last Puritan, often slogged opaquely. I have no aptitude or use for academic philosophy, where Santayana made his career. He couldn’t quite admit his homosexual longings, to his discredit. His autobiography, while a plum-cake of perceptions, meanders too long and feels evasive, while crowing about its candor. Having often vowed to shelve Santayana and move on, I found myself returning. Why?

With writers who entwine me, I’ve developed an M.O., that enables me to deepen our acquaintance without surrendering to the demands of expertise. I am way too curious and restless to be monogamous in my literary passions: like Don Giovanni with his romances, my list of lovelies is long. Yet I crave a closer embrace than a single reading permits, to know these makers better. To that end, I undertake an excursion of extraction, plucking from my reading an array of morsels, which, taken together, evoke the person: a sort of mosaic out of snippets. I do this for myself, sometime sharing the result. I’ve performed this operation on Montaigne, Jane Austen, Francis Bacon, Spinoza, and Kierkegaard, among others, so when I need them, I can more readily recall them to mind. Otherwise, when I shut their books, they’d vanish, for my memory is weak. Some authors resist this reductive treatment, storytellers especially, whose effect depends as much on their characters’ evolution as the elegance of their language. Dr. Johnson and Thoreau are too copious to shrink to a dozen pages: I revert to them entire, with clock-like regularity

Reviewing this sampler from Persons and Places (which took me only five years to finish reading), Santayana emerges more brilliant, poignant, and courageous than I’d allowed. Few souls struggled so diligently and capably to discover what it meant to be alive. Yes, he irks me at times, but what a mentor, brother, brother-in-arms!

*

I feel a natural sympathy with unprejudiced minds, or if you like with rogues. I have never been adventurous: I need to be quiet in order to be free. I at least have found that old age is the time for happiness, even for enjoying in retrospect the years of youth that were so distracted in their day. If clearness about things produces a fundamental despair, a fundamental despair in turn produces clearness or even playfulness about ordinary matters. I was a spontaneous modernist in theology and philosophy: but not being pledged, either socially or superstitiously, to any sect or tradition, I was spared the torments of those poor Catholic priests or those limping Anglicans who think they can be at once modernists and believers. They can only be amateurs, at best connoisseurs, in religion. The rest for them will be only a belated masquerade. The fiercest spirit must have some birthplace, some locus standi from which to view the world and some innate passion by which to judge it. Spirit must always be the spirit of some body. One world is enough, to my feeling, and I should wish religion to digest and transmute this life into ultimate spiritual terms rather than commit us to fresh risks, ambitions, and love-affairs in a life to come. I … love the earth and hate the world. I don’t understand how a rational being can be wrong in doing or being what he fundamentally wishes to be or to do… Experience and philosophy have taught me that perfect integrity is an ideal never fully realized, that nature is fluid and inwardly chaotic in the last resort, even in the most heroic soul; and I am ashamed and truly repentant if ever I find that have been dazed and false to myself either in my conduct or opinions. In this sense, I am not without a conscience; but I accept nobody’s precepts traversing my moral freedom. That “producer’s economy”, then beginning to prevail in America,… first creates articles and then attempts to create a demand for them. (This) economy has flooded the country with breakfast foods, shaving soaps, poets, and professors of philosophy. (Note: Santayana was both professor and poet.) A man’s memory may almost have become the art of continually varying and misrepresenting his past, according to his interests in the present. This, when it is not intentional or dishonest, involves no deception. Things truly wear those aspects to one another. A point of view and a special lighting are not distortions. They are conditions of vision, and spirit can see nothing not focused in some living eye. More than once in my life I have crossed a desert in all that regards myself, my thoughts, or my happiness, so that when I look back over those years, I see objects, I see public events, I see persons and places, but I don’t see myself… Of myself in those years I have no recollection: it is as if I hadn’t existed, or only as a mechanical sensorium and active apparatus, doing its work under any name. Somnambulistic periods, let me call them. My apprehension of words is auricular; I must hear what I read. I am acutely conscious… of my great defects, bodily, passional, intellectual and moral. I am in almost everything the opposite of what I should have wished to be. In solitude it is possible to love mankind; in the world, for one who knows the world, there can be nothing but secret or open war. For those who love war the world is an excellent field, but I am a born cleric or poet. I must see both sides and take neither, in order, ideally, to embrace both, to sing both, and love the different forms that the good and the beautiful wear to different creatures. Between the laughing and the weeping philosopher there is no opposition: the same facts that make one laugh, make one weep. That the real was rotten and only the imaginary at all interesting seemed to me axiomatic. That was too sweeping, yet allowing for the rash generalizations of youth, it is still what I think. My philosophy has never changed. My English was too literary, too correct [to write comically]; and I never acquired, or liked, the American art of perpetual joking. There are phases of distress when help is neither possible nor desired. It is simpler, easier, more honest to be seasick alone, and to die alone. Your genuine and profound sceptic sees no reason to quarrel with any ruling orthodoxy. It is as plausible as any other capable of prevailing in the world. It was not our fault that we were born. Is it our fault that we believe what we believe? To be incurious and at peace in such matters might even be a mark of profound faith, if the intention were to conform to the divine order or things in courage and silence, without knowing what precisely this order may be. What I wanted was to go on being a student, and especially to be a travelling student. I loved speculation for itself, as I loved poetry, not out of worldly respect or anxiety lest I should be mistaken, but for the splendor of it, like the splendor of the sea and the stars. Baroque and rococo cannot be foreign to a Spaniard. They are profoundly congenial and Quixotic, suspended as it were between two contrary insights: that in the service of love and imagination nothing can be too lavish, too sublime, or too festive; yet that all this passion is a caprice, a farce, a contortion, a comedy of illusion. [Your) typical Yankee [is] cold shrewd and spare inwardly, smiling with a sort of insulated incredulity at everything passionate, as if he lived inside a green glass bottle. A string of excited, fugitive, miscellaneous pleasures is not happiness; happiness resides in imaginative reflection and judgement: when the picture of one’s life, or of human life, as it truly has been or is, satisfies the will and is gladly accepted. I began to prepare for my retirement from teaching before I had begun to teach. We laughed at the same things and we liked the same things. What more is needed for agreeable society? Think what an incubus life would be, if death were not destined to cancel it… That is the very image of hell. But natural life, life with its ascending and descending curve, is a tempting adventure; it is an open path; curiosity and courage prompt one to try it. Moreover, the choice must have been made for us before it can be offered; we are already alive, and a whole world of creatures is alive, like us. The first question is therefore what this world might bring to light, for others and for ourselves, as long as it endures. Therefore the preference for life is, as [my friend] felt, a duty, as well as a natural sporting impulse. Modern life is not made for friendship: common interests are not strong enough, private interests are too absorbing. The leaders [in Boston society in the 1880’s] were “business men,” and weight in the business world was what counted in their estimation. Of course there must be clergymen and doctors also, and even artists, but they remained parasites, and not persons with whom the bulwarks of society had any real sympathy. Lawyers were a little better, because business couldn’t be safeguarded without lawyers, and they often were or became men of property themselves; but politicians were taboo; and military men, in Boston, non-existent. Lectures, like sermons, are usually unprofitable. Philosophy can be communicated only by being evoked; the pupil’s mind must be engaged dialectically in the discussion. Otherwise all that can be taught is the literary history of philosophy, that is, the phrases that various philosopher have rendered famous. I believe, compulsorily and satirically, in the existence of this absurd world; but as to the existence of a better world, or of hidden reasons in this one, I am incredulous, or rather I am critically skeptical; because it is not difficult to see the familiar motives that lead men to invent such myths. That a man has preferences and can understand and do one thing better than another, follows from his inevitable limitations and definite gifts: but that which marks progress in his life is the purity of his art; I mean, the degree to which his art has become his life, so that the rest of his nature does not impede or corrupt his art, but only feeds it. Religion was poetry intervening in life. I have ultimately become a sort of hermit, not from fear or horror of mankind, but by sheer preference for peace and obscurity. Fortune has become indifferent to me, except as fortune might allow me to despise fortune and to live simply in a beautiful place. I have cut off all artificial society, reducing it to the limits of sincere friendship or intellectual sympathy. It is dishonest and self-contradictory to forswear your honest loves, past or present. They it is that reveal your true nature and its possible fulfillments; they are the Good. The truth of life could be seen only in the shadow of death: living and dying were simultaneous and inseparable. You will do the least harm and find the greatest satisfactions, if, being furnished as lightly as possible with possessions, you live freely among ideas. If we wish to be something perfect, we must banish regret for not being anything else. All my life I have dreamt of travels, possible and impossible: travels in space and travels in time, travels into other bodies and into alien minds. Not having been suffered by fate to be more than an occasional tripper and tourist, I have taken my revenge in what might be called travels of the intellect, by admitting the opposite of all facts and beliefs to be equally possible and no more arbitrary. These travels of the intellect helped me in boyhood to overcome the hatred that I then felt for my times and my surroundings; and later they have helped me to overcome the rash impulse to claim an absolute rightness for the things I preferred… The born traveler is not pining for a better cage. If ever he got to heaven, on the next day he would discover its boundaries, and on the third day he would make a little raid beyond them. Imagination is potentially infinite… The precision and variety of alien things fascinate the traveler. He is aware that however much he may have seen, more and greater things remain to be explored, at least ideally; and he need never cease traveling, if he has a critical mind… In a world where the exotic abounded, to ignore it would be ignominious intellectually and practically dangerous; because unless you understand and respect things foreign, you will never perceive the special character of things at home or of your own mind… Travel, therefore, I said to myself, travel at least in thought, or else you are likely to live and die an ass… The traveler must possess fixed interests and faculties, to be served by travel. If he drifted aimlessly from country to country he would not travel, but only wander, ramble, or tramp. The traveler must be somebody and come from somewhere, so that his definite character and moral traditions may supply an organ and a point of comparison for his observations… The traveler should be an artist, recomposing what he sees; then he can carry away the picture and add it to a transmissible fund of wisdom, not as further miscellaneous experience but as a corrected view of the truth. Doric purity is not a thing to be expected again in history, at least not yet. It indicates a people that knows its small place in the universe and yet asserts its dignity. Both Lucretius and Empedocles are said to have killed themselves, or voluntarily become gods; in any case they saw the world as the gods would; in other words, as we all should if we could surmount our accidental humanity and let the pure spirit in us speak through our words. Unattached academic obscurity is rather a blessed condition, when it doesn’t breed pedantry, envy, or ill-nature. I had never wished to teach. I had nothing to teach. I wished only to learn, to be always the student, never the professor. And with being eternally the student went the idea of being free to move, to pass from one town and one country to another, at least while enough youth and energy remained for me to love exploration and to profit by it. I am profoundly selfish in the sense that I resist human contagion, except provisionally, on the surface, and in matters indifferent to me. For pleasure and convivially, I like to share the life about me, and have often done it: but never so as, at heart, to surrender my independence. (Santayana’s tragic deficiency, in my view.) Italy and Rome were… my ideal point of vantage in thought, the one anthropological center where nature and art were most beautiful, and mankind least distorted from their ideal character. The great question is not what age you live in or what art you pursue, but what perfection you can achieve in that art under these circumstances. The contemporary world has turned its back on the attempt and even on the desire to live reasonably… What is requisite for living rationally? I think the conditions can be reduced to two: First, self-knowledge, the Socratic key to wisdom; and second, sufficient knowledge of the world to perceive what alternatives are open to you and which of them are favorable to your interests… [Modern] society lacked altogether that essential trait of rational living, to have a clear, sanctioned, ultimate aim. The cry was for vacant freedom and indeterminate progress. Every generation is born as ignorant and willful as the first man; and when tradition has lost its obvious fitness or numinous authority, eager minds will revert without knowing it to every false hope and blind alley that had tempted their predecessors.” (Another way of saying – Santayana’s most quoted aphorism – “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”)

Those who cannot remember Santayana are condemned to reread him?

Thanks for this sampler.